Yet to have the religion of eboga begin with these mild-mannered little people is in striking contrast with the giant personages and the struggles with giants and monsters which appear in the traditional legend

Fernandez, James W. Bwiti An Ethnography of the Religious Imagination in Africa. Princeton University Press

…

Umieszczenie początków religii ebogi wśród tych łagodnych, drobnych ludzi uderza kontrastem z wielkimi postaciami i ich wielkimi bitwami z gigantami i potworami jakie zwykle mamy w tradycyjnej legendzie.

Here is a Pygmy legend that goes something like this:

In the beginning the prime spirit created the world and all that inhabited it. The prime spirit saw that all was good and crossed the barrier back to the void, referred to by the Pygmy’s as the Kungala. Back in the void, the prime spirit realized it was lonely and returned to view it’s creation. The prime spirit looked down and saw a Pygmy climbing a fruit tree to collect food. The prime spirit shook the tree until the Pygmy fell to ground, dying on impact. The prime spirit latched onto the Pygmy’s spirit and took it back across the Kungala into the void and was no longer lonely.

…

Oto pigmejska opowieść, jedna z kilku na ten temat :

Na początku najwyższy duch stworzył świat i wszystko co go zamieszkiwało. Duch zobaczył iż wszystko było w porządku, i przekroczył granicę wracając do próżni, pustki jaką Pigmeje nazywają Kungala. Będąc już tam, najwyższy duch zdał sobie sprawę ze swej samotności i powrócił aby oglądać swoje stworzenie. Spojrzał w dół i zobaczył Pigmeja wspinającego się na owocowe drzewo w poszukiwaniu pożywienia. Duch zatrząsł drzewem aż Pigmej spadł na ziemię, ginąc na miejscu. Najwyższy duch wpiął się w ducha Pigmeja i zaniósł go do siebie do Kungali i nie był już samotny.

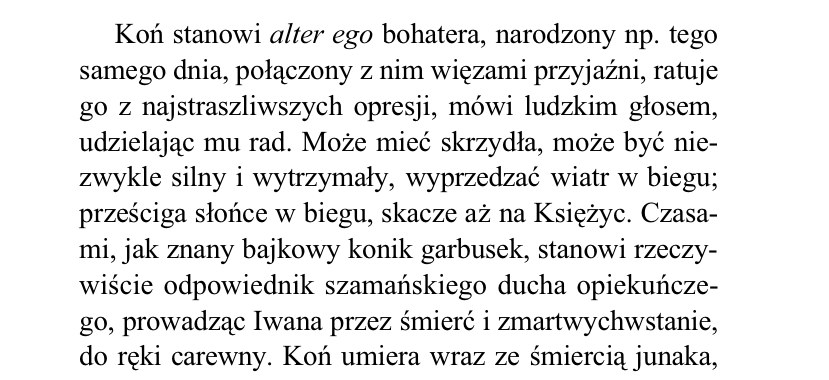

Meanwhile, back on earth, a few Pygmy’s came across the body of the Pygmy, and never having seen a dead Pygmy body, they decided to bury it on the spot. They dug a hole, wrapped it in a cat skin and filled the grave.

Some time passed and the Pygmy’s partner came to the grave and noticed a couple plants growing from the grave that she had never seen before. As she sat there, one of the plants spoke to her: If you eat from my roots you may visit your dead partner. After chewing the bitter roots, she left her body and crossed the Kungala into the void and met up with her partner and The prime spirit. She spent some time there, learning what had happened and eventually returned to her body with knowledge never before possessed by a Pygmy.

…

W międzyczasie na Ziemi kilku Pigmejów natrafiło na ciało Pigmeja, i jako że nigdy wcześniej nie widzieli martwego pigmejskiego ciała, postanowili od razu je zakopać. Zrobili dziurę w ziemi, zawinęli ciało w skórę dzikiego kota i zasypali grób.

Minęło trochę czasu, partnerka Pigmeja przyszła na grób i zauważyła parę roślin wyrastającą z grobu, roślin jakich nigdy wcześniej nie widziała. Gdy usiadła, jedna z nich przemówiła do niej : Jeżeli zjesz moje korzenie, możesz odwiedzić swojego martwego ukochanego. Po żuciu gorzkiego korzenia opuściła swe ciało i przekroczyła granicę Kungali, gdzie spotkała swego partnera i najwyższego ducha. Spędziła tam trochę czasu, próbując zrozumieć co się stało, i ostatecznie powróciła do ciała z wiedzą jakiej nie posiadał wcześniej żaden Pigmej.

Being a female, eating of a sacred plant was taboo to the Pygmy’s and she was cast out of the tribe. But curiosity was at hand and as time passed and the Iboga plant propagated, the Pygmy’s began to ingest the root bark to cross the Kungala and visit their ancestors.

As the story goes, the other plant that grew from the grave differs from different Pygmy sources, some lore says it was ganja, some say it was a psychoactive mushroom.

…

Ponieważ była kobietą, zjedzenie przez nią świętej rośliny było dla Pigmejów złamaniem tabu i została wygnana z plemienia. Ale ciekawość pozostała i z czasem iboga rozprzestrzeniła się i Pigmeje zaczęli używać kory korzenia do podróży do Kungali i odwiedzin ich przodków.

Według tej historii, są różne wersje co do tego, czym była druga roślina z rosnących na grobie – według jednych to ganja, według innych Duna, psychoaktywny grzyb.

(…) There is one final attraction in Pygmy life [ for the Bwiti from Fang tribe, who confirm the Pygmy origin of their cult ] . From a Fang perspective, preoccupied as Fang are with “bad body” or “obscure body” , the Pygmies living in the forest are a pure people. They do not have the sins, either ritual or social, of the village. The Pygmies regularly inhabit those desolate and abandoned areas of the forest where troubled and impure Fang have always gone to sit for days and nights (dzobege efun) confessing their sins and obtaining purity of body (nyol nfouban).

Fernandez, James W. Bwiti An Ethnography of the Religious Imagination in Africa. Princeton University Press

…

(…) Jest jeszcze jedna pociągająca rzecz w życiu Pigmejów [ dla Bwiti z plemienia Fang, którzy potwierdzają pigmejskie pochodzenie swojego kultu ]. Z perspektywy Fangów, przejmujących się nieustannie “złym ciałem” czy “niejasnym ciałem”, Pigmeje żyjący w lesie są czystymi ludźmi. Nie mają grzechów, czy to rytualnych czy społecznych, wynikających z życia w wiosce. Pigmeje zwykle zamieszkują te odludne ostępy w lesie gdzie skalani Fangowie zawsze udawali się aby przez dni i noce spowiadać się i uzyskać czystość ciała (nyol nfouban).

“The appearance of little people at transitional moments in myth and legend is a widespread motif in world folklore and recurrent in western Equatorial Africa. Quite apart from their marginality as forest inhabitants, which gives them valence at transitional moments, Pygmies, more particularly, derive power from a paradox in their physical presentation. The transition which this origin legend describes from a state of spiritual isolation to intercommunication-the principal transformation aimed at in Bwiti is effectively accomplished by little people who combine in themselves, paradoxically, a neoteny reminiscent of childhood and infancy with the actuality of full adulthood. Pygmies and other little people are good physical representations-a living condensation–of what the ancestor cult is all about: the establishing of a link between parents and child, grandparents and grandchild.”

Fernandez, James W. Bwiti An Ethnography of the Religious Imagination in Africa. Princeton University Press

…

“Pojawienie się małych ludzi w zwrotnych momentach mitów i legend jest częstym motywem w światowym folkorze także powracającym w zachodniej Afryce równikowej. Poza ich marginalnym statusem jako mieszkańców lasu, który daje im znaczenie w momentach przejściowych, Pigmeje czerpią swoją moc z paradoksu ich fizycznego wyglądu. Przejście, opisywane przez legendę, ze stanu duchowej izolacji do interkomunikacji – główna transformacja jaką chce osiągnąć praktyka Bwiti – jest osiągane efektywnie przez małych ludzi, którzy łączą w sobię neotenię przypominającą dzieciństwo z rzeczywistym stanem dorosłości. Pigmeje i inni mali ludzie są dobrą fizyczną reprezentacją – żywą kondensacją – tego wszystkiego czym jest kult przodków – ustanowienia komunikacji między rodzicami i dziećmi, dziadkami i wnukami”

Fernandez, James W. Bwiti An Ethnography of the Religious Imagination in Africa. Princeton University Press