The healing happens when the cosmic order is re-established, that is the traditional and forgotten view, in which the macrocosm and microcosm of the individual are interconnected, and so one can be healed by healing another, these actions are complementary, and are in a way re-creation of the world.

…

Uzdrowienie ma miejsce kiedy przywrócony zostaje kosmiczny porządek, taki jest tradycyjny i zapomniany nieco pogląd, według którego makrokosmos i mikrokosmos chorego są połączone, i jedno zatem może byc uzdrowione przez uzdrowienie drugiego, te działania są komplementarne, i są w pewnym sensie stwarzaniem świata na nowo.

Mfonga mfonga o bele ening ase oh!

(R) Oh, Oh, ening ase oh, oh.

The wind, the wind. It has all of life.

(R) Oh, Oh. All of life. Oh, Oh.

…

O wiatr, wiatr. Całe w nim jest życie!

(R) Oh, oh, Całe życie, oh oh.

Bwiti creation songs begin with wind and water and the creator gods. Life’s movement is contained in the wind which is the essence of movement. The word mfonga (wind, air, breath) is associated with “spirit” in the Western sense and hence with the Holy Spirit. Thus Banzie interpret this song as referring to the Holy Spirit which was, primordially, the principle of life.

…

Pieśni stworzenia Bwiti rozpoczynają się motywem wiatru, wody i bogów stworzycieli. Ruch życia zawarty jest w wiatrze, który jest esencją ruchu. Słowo mfonga ( wiatr, powietrze, oddech ) jest łączone z “duchem” w rozumieniu Zachodu, a zatem z Duchem Świętym. Banzie, inicjowani, interpretują tą pieśń jako mówiącą o Duchu Świętym, który był pierwotną zasadą życia.

In the beginning were words, said Muye, and these words were lonely. And because of this loneliness the creator god, Mebege, created the path of life. This was later to become the path of birth and death, the path upon which all Bwiti rituals tread.

…

Na początku były słowa, powiedział Muye, i słowa te były samotne. Z powodu tej samotności bóg stworzyciel, Mebege, uformował ścieżkę życia. Ta później stać się miała ścieżką życia i śmierci, ścieżką po której ruch odtwarzają wszystkie rytuały Bwiti.

The group of Banzie returned to the origin spot for the third song of entrance:

Nkobo wa kane yan, o nto ngap ele.

Mfonga esa, edo e ne monenyang menzim

(R) Menzim e ne monenyang.

The words have divided up things, there are three divisions.

The wind is the father, the older brother of the water.

(R) Water is a brother.

…

Grupa Banzie powraca do miejsca początku, by zaśpiewać trzecią z pieśni wejścia :

Słowa podzieliły rzeczy, są trzy części

Wiatr jest ojcem, starszym bratem wody.

(R) Woda jest bratem.

The “three divisions” referred to here are the three persons within the Cosmic Egg which the creator god Mebege, through the agency of sky spider, lowered to the water: Zame ye Mebege (God), his sister Nyingwan Mebege, and his brother Nlona Mebege.

…

Trzy części o jakich mówi pieśń to trzy osoby wewnątrz Kosmicznego Jaja, które Mebege, bóg stworzyciel, poprzez działanie niebieskiego pająka, obniżył ku wodom : Zame ye Mebege ( Bóg ), jego siostra Nyingwan Mebege i jego brat ( wąż ) Nlona Mebege.

Nkol o bele ening, mfonga oyo, menzim asi.

(R) Nkol o bele ening.

The filament (cord) holds life, wind above, water below.

(R) The cord holds life.

The reference is to sky spider’s filament as it lowered the egg containing “life in three persons” to the sea. But this song in other contexts refers to the line of umbilical cords which are imagined to attach the worshiper genealogically through his ancestors ascendent to the great gods.

…

Ta nić / struna / podtrzymuje życie, wiatr powyżej, woda poniżej.

(R) Nić trzyma życie.

Chodzi tu o nić utkaną przez kosmicznego pająka, na której opuszczał ku morzu jajo zawierające “życie w trzech osobach”. Ale pieśń ta, przy innych okazjach, odnosi się do linii pępowin, które łączą wyznawcę poprzez kolejnych przodków ku wielkim bogom.

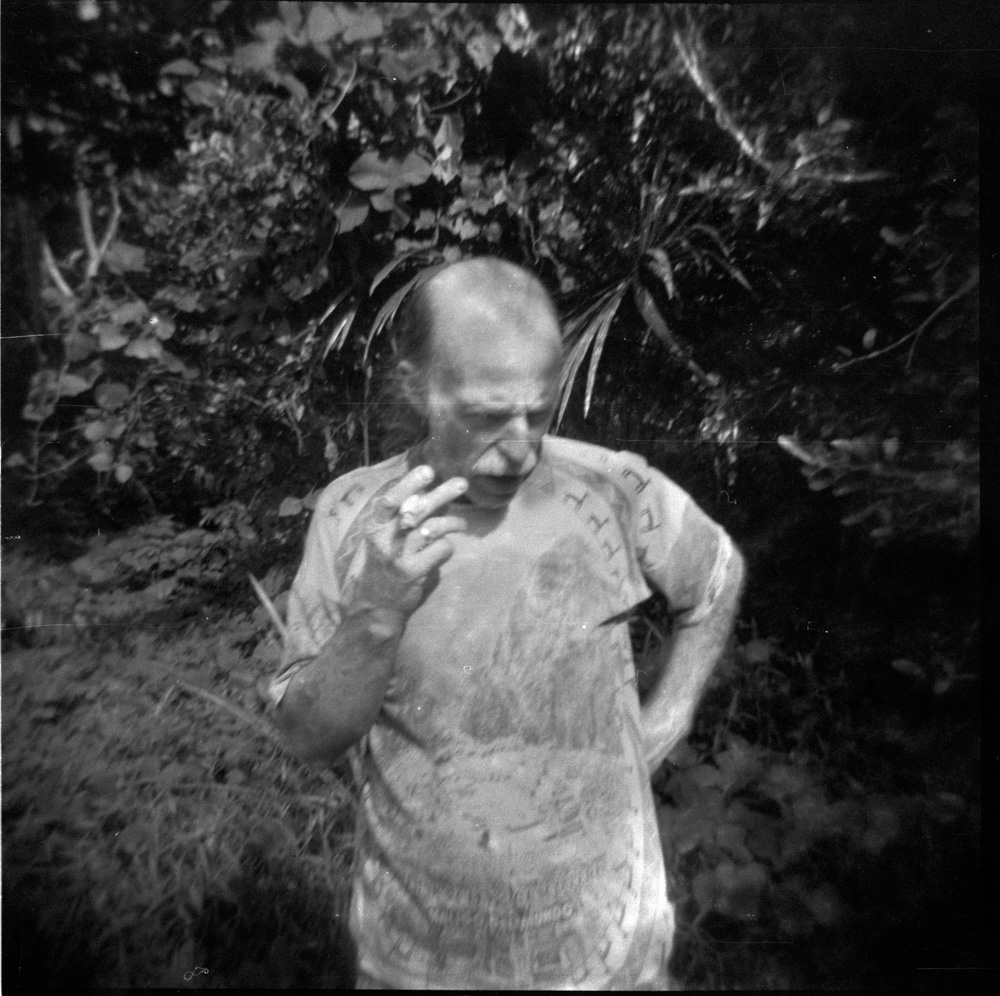

[ Photos from healing ceremony in Bwiti cult in Cameroon, text includes excerpts from Fernandez, James W. Bwiti An Ethnography of the Religious Imagination in Africa. Princeton University Press /// Zdjęcia z ceremonii uzdrawiania w tradycji psychodelicznego kultu Bwiti w Kamerunie, tekst na podstawie Fernandez, James W. Bwiti An Ethnography of the Religious Imagination in Africa. Princeton University Press ]