based on Joseph Cambell, Creative Mythology, in “Masks of God” series, pages 626-631 /// tekst na podstawie ostatniej części serii “Maski Boga” autorstwa Josepha Campbella, “Twórcza mitologia”, strony 626-631

Traditionally, as our survey of the myths of the world has disclosed, the idea of an absolute ontological distinction between God and man – or between gods and men, divinity and nature – first became an important social and psychological force in the Near East, specifically Akkad, in the period of the first Semitic kings, c. 2500 B.C.

…

Jak pokazał dotąd nasz przegląd mitów świata, idea absolutnego ontologicznego rozróżnienia pomiędzy Bogiem i człowiekiem, czy też pomiędzy bogami i ludźmi, boskością i naturą, po raz pierwszy nabrała społecznej i psychologicznej mocy na Bliskim Wschodzie, konkretnie w królestwie Akkad, w okresie pierwszych semickich królów, około 2500 r p.n.e

Then and there it was that the older, neolithic and Bronze Age mythologies of the Goddess Mother of the universe, in whom all things have their being, gods and men, plants, animals, and inanimate objects alike, and whose cosmic body itself is the enclosing sphere of space-time within which all experience, all knowledge, is enclosed, were suppressed and set aside in favor of those male-oriented, patriarchal mythologies of thunder-hurling warrior gods that by the time a thousand years had passed, c. 1500 B.C., had become the dominant divinities of the Near East.

…

To właśnie wtedy i tam starsze, neolityczne i pochodzące z epoki brązu mitologie Bogini Matki wszechświata, w której żyją wszystkie rzeczy, bogowie i ludzie, rośliny, zwierzęta i cała materia, i której kosmiczne ciało jest sferą czasoprzestrzeni w której zamyka się całe doświadczenie i cała wiedza, te mitologie zostały wyparte i odrzucone, a ich miejsce zajęły męskie, patriarchalne mity miotających piorunem wojowniczych bogów, którzy w czasie upływu tysiąca lat, do ok 1500 r p.n.e stali się dominującymi władcami bliskowschodniego panteonu.

The Aryan warrior herdsmen, driving downward from the north into Anatolia, Greece, and the Aegean isles, as well as west to the Atlantic, were also patriarchal in custom, worshiping gods of thunder and war. In contrast to the Semites, however, they never ranked ancestral tribal gods above the gods of nature, or separated divinity from nature…

…

Aryjscy wojownicy – pasterze, gnający z północy na tereny Anatolii, Grecji, wysp Egejskich, jak i na zachód aż po Atlantyk także kultywowali patriarchalne zwyczaje, czcili bogów grzmotu i wojny. W przeciwieństwie do Semitów jednak nigdy nie wywyższyli plemiennych bożków przodków ponad bogów natury ani nie rozdzielili boskości od natury …

…whereas among the Semites in their desert homeland, where nature-Mother Nature-had little or nothing to give and life depended largely on the order and solidarity of the group, all faith was placed in whatever god was locally recognized as patron-father of the tribe. “All Semitic tribes,” declares one distinguished authority in this field, the late Profesor S. H. Langdon of Oxford, “appear to have started with a single tribal deity whom they regard as the divine creator of his people.” ( hence – “don’t worship other gods”, not that “there are no other gods” )

…

… podczas gdy wśród Semitów w ich pustynnych ojczyznach, gdzie natura – Matka Natura – miała mało albo nic do zaoferowania i przetrwanie zależało głównie od porządku i solidarności w grupie, cała wiara została skierowana na któregolwiek z bogów jakiego lokalnie uznano jako patrona – ojca plemienia. “Wszystkie semickie plemiona”, jak stwierdza jeden z wybitnych autorytetów na tym polu, profesor S.H.Langdon z Oksfordu,”zdają się mieć na początku jedną plemienną boską postać, którą uznają jako stworzyciela swojego ludu” ( stąd – “nie miej innych bogów przed mną” a nie “nie ma innych bogów” )

The laws by which men lived, therefore, were not the laws of nature, universally revealed, but of this little tribe or that, each special to itself and derived from its own mythological first father.

…

Prawa według jakich ci ludzie żyli nie były więc prawami natury, uniwersalnie objawianymi w róznych kontekstach kulturowych, ale tego lub innego plemienia, każde odrębne, wywiedzione od swego mitologicznego pra-ojca.

The outstanding themes of this Syro-Arabian desert mythology, then, we may summarize as follows: 1. mythic dissociation, God as transcendent in the theological sense defined above, and the earth and spheres, consequently, as mere dust, in no sense “divine”; 2. the notion of a special revelation from the tribal father- god exclusively to his group, the result of which is 3. a communal religion inherently exclusive, either as in Judaism, of a racial group, or as in Christianity and Islam, credal, for and of those alone who, professing the faith, participate in its rites. Still further, 4. since women are of the order rather of nature than of the law, women do not function as clergy in these religions, and the idea of a goddess superior, or even equal, to the authorized god is inconceivable. Finally, 5. the myths fundamental to each tribal heritage are interpreted historically, not symbolically (…)

…

Wyróżniające się motywy w bliskowschodniej pustynnej mitologii możemy podsumować następująco : 1. mityczna dysocjacja, Bóg jest transcendentny w teologicznym sensie wcześniej zdefiniowanym, a ziemia marnym pyłem, w żadnym sensie nie jest “boska” ; 2. idea szczególnego objawienia plemiennego boga – boga wyłącznie dla tej grupy, czego rezultatem jest 3. wspólna religia z samego założenia ekskluzywna – ograniczona jak w wypadku judaizmu, do grupy etnicznej, albo jak w wypadku chrześcijaństwa i islamu, do podpisujących się pod credo, tylko dla tych którzy wyznają konkretną wiarę, i uczestniczą w jej rytuałach. Kolejne to 4. skoro kobiety przynależą raczej do porządku natury niż prawa, nie pełnią oficjalnych funkcji w tychże religiach, i idea bogini wyższej, a nawet równej jedynemu autoryzowanemu bogu jest nie do pomyślenia. Wreszcie na koniec, 5. prawa fundamentalne dla konkretnego, własnego plemiennego dziedzictwa interpretuje się historycznie a nie symbolicznie (…)

In the earlier, Bronze Age order, on the other hand – which is fundamental to both India and China, as well as to Sumer, Egypt, and Crete – the leading ideas, we have found, were : the ultimate mystery as transcendent of definition yet immanent in all things; (…) the universe and all things within it as making multifariously manifest one order of natural law, which is everlasting, wondrous, blissful, and divine, so that the revelation to be recognized is not special to any single, super- naturally authorized folk or theology, but for all, manifest in the universe (macrocosm) and every individual heart (microcosm)

…

We wcześniejszym porządku epoki brązu z kolei – stanowiącym podstawy zarówno kultury Indii, Chin jak i Sumeru, Egiptu i Krety – wiodące idee jakie odkryliśmy były następujące : najgłębsza tajemnica jest transcedentna z definicji a zarazem obecna we wszystkim , (…) wszechświat i wszystkie rzeczy w nim zawarte w nieskończonej różnorodności manifestują jeden porządek naturalnego prawa, które jest wieczne, cudowne, błogie i nacechowane boskością, tak więc objawienie jakiego tu szukamy nie przynależy jednej, konkretnej, namaszczonej przez nadnaturalną siłę teologii czy tradycji ale wszystkim – i jest obecne we wszechświecie ( makrokosmosie ) i każdym pojedynczym sercu ( mikrokosmosie )

(…) Now it can hardly be said of the Christian cult, which sprang into being in this ( Middle Eastern ) environment and was carried thence to Europe, that it was “brought forth” from the substance, life experiences, reactions, sufferings, and realizations of any of the peoples on whom it was impressed. Its borrowed symbols and borrowed god were presented to these as facts; and by the clergy claiming authority from such facts every movement of the native life to render its own spiritual statement was suppressed. Every local deity was a demon, every natural thought, a sin. So that no wonder if the outstanding feature of the Church’s history in the West became the brutality and futility of its increasingly hysterical, finally unsuccessful, combats against heresy on every front!

…

(…) Niezupełnie da się powiedzieć o chrześcijańskim kulcie, który wyrósł na tym bliskowschodnim podłożu, i został póżniej eksportowany do Europy, że “wydobyty” został z istoty, życiowych doświadczeń, reakcji, cierpień i uświadomień którychkolwiek z tych ludów którym został wdrukowany. Jego pożyczone symbole i pożyczony bóg zostały zaprezentowane jako historyczne fakty, a kler opierający swój autorytet na rzekomej autentyczności tych faktów zajął się tłumieniem jakichkolwiek rdzennych ruchów próbujących własnych duchowych poszukiwań. Każdy lokalny bóg stał się demonem, każda rdzenna forma myśli – grzechem. Nie jest więc dziwne, że najbardziej charakterystyczna cecha w historii kościoła na zachodzie to brutalność jak i bezsens jego coraz bardziej histerycznej a ostatecznie nieskutecznej wojny z herezją na każdym froncie !

On the popular side, in their popular cults, the Indians are, of course, as positivistic in their readings of their myths as any farmer in Tennessee, rabbi in the Bronx, or pope in Rome. Krishna actually danced in manifold rapture with the gopis, and the Buddha walked on water. However, as soon as one turns to the higher texts, such literalism disappears and all the imagery is interpreted symbolically, as of the psyche.

We read in the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad:

“Whoever knows “I am brahman!” becomes this All, and not even the gods can prevent his becoming thus, for he becomes their very Self. But whoever worships another divinity than his Self, supposing “He is one, I am another,” knows not. He is like a sacrificial beast for the gods. And as many animals would be useful to a man, so is even one such person useful to the gods. But if even one animal is taken away, it is not pleasant. What then, if many? It is not pleasing to the gods, therefore, that people should know this.”

…

W swoich popularnych, ludowych odmianach religii Hindusi są oczywiście tak pozytywistyczni w swym odczytywaniu mitów jak jakikolwiek farmer z Tenessee, rabin z Bronxu czy papież z Rzymu. Kryszna dosłownie tańczył w uniesieniu w konkretnym historycznym momencie a Budda chodził po wodzie. Jednak wystarczy zajrzeć do wyższych tekstów, i taka dosłowność znika a obrazy są interpretowane symbolicznie, jako metafory psyche.

Czytamy w Upaniszadach, wieki przed Chrystusem :

Ktokolwiek wie “Ja jestem Brahman!”, staje się tym Wszystkim, i nawet bogowie nie mogą go od tego stawania powstrzymać, bo on staje się nimi. Ale ktokolwiek czci jakąś inną boskość niż Jaźń, zakładając “On jest tym, a ja czym innym”, ten błądzi. Jest jak ofiarna zwierzyna dla bogów. I tak jak wiele zwierząt byłoby użytecznych człowiekowi, tak i nawet jedna taka osoba jest użyteczna bogom. Ale jeżeli nawet jedno zwierze jest zabrane, nie jest to przyjemnym. Cóż wtedy, kiedy wiele? Nie jest to miłe bogom, zatem, żeby ludzie poznali prawdę”

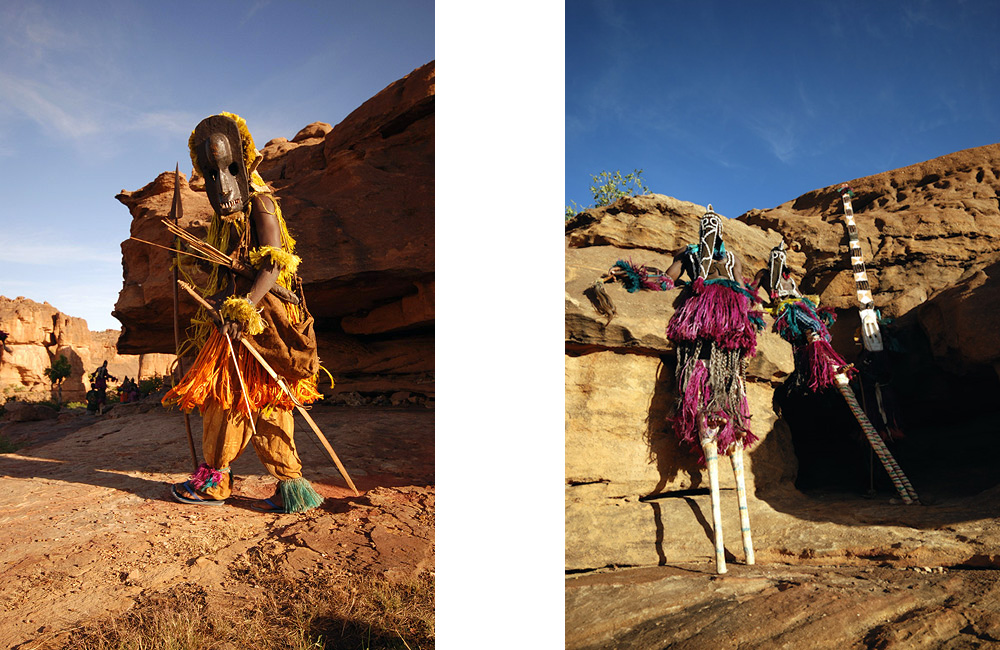

[ Photos : Mali, Polish folk catholic shrines, Mongolia, the Amazon and India / Zdjęcia z : Mali, Lichenia i Jasnej Góry, Amazonii i Indii ]